Staying Healthy in Immigrant Pakistani Families Living in the United States

- Inquiry commodity

- Open Admission

- Published:

Social networks, health and identity: exploring culturally embedded masculinity with the Pakistani community, West Midlands, United kingdom

BMC Public Wellness volume xx, Article number:1432 (2020) Cite this article

Abstract

Background

Migrants from Southward Asia living in adult countries accept an increased risk for developing cardiovascular affliction (CVD), with express inquiry into underlying social causes.

Methods

Nosotros used social majuscule as an interpretive lens to undertake analysis of exploratory qualitative interviews with 3 generations of at-risk migrant Pakistani men from the West Midlands, United kingdom. Perceptions of social networks, trust, and cultural norms associated with access to healthcare (support and information) were the primary area of exploration.

Results

Findings highlighted the role of social networks within religious or community spaces embedded every bit office of ethnic enclaves. Local Mosques and gyms remained cardinal social spaces, where culturally specific gender differences played out within the context of a diaspora community, defined ways in which individuals navigated their social spheres and influenced members of their family and community on health and social behaviours.

Conclusions

There are generational and age-based differences in how members use locations to access and develop social back up for detail lifestyle choices. The pursuit of a healthier lifestyle varies beyond the diverse migrant community, determined by social hierarchies and socio-cultural factors. Living close to similar others can limit exposure to novel lifestyle choices and efforts demand to exist made to promote wider integration between communities and variety of locations catering to wellness and lifestyle.

Groundwork

The growing prevalence of obesity alongside co-morbidities such every bit diabetes and cardiovascular illness (CVD) crave global preventative action [1]. At greater run a risk are migrants, where the motion of people across borders coincides with changing wellness beliefs and behaviours [2].

In the UK, the 10-year NHS plan highlighted the need for greater support in Black and Minority Ethnic (BAME) communities to address specific wellness needs through lifestyle services which later led to increased funding to further develop the Diabetes Prevention Program [iii]. Given that 65% of men were classified as overweight or obese in 2016 (in the UK), in that location is a clear demand to increase men's access to lifestyle services [4].

Neighbourhood studies in the Great britain have shown minority-ethnic groups are over-represented in deprived areas characterised by disadvantaged physical environments, including inadequate leisure facilities, housing, and over stretched primary and secondary healthcare facilities [ 5, half-dozen]. The worst neighbourhood environment for the White majority is comparatively better than that of minority-ethnic groups in the UK [6, 7].

The Pakistani community

The South Asian diaspora is one of the largest migrant groups within loftier-income countries, with the largest community in Europe residing in the United Kingdom (1,174,983 out of 2,255,000 Pakistanis in Europe living in the U.k.) [8]. Nonetheless, the health behaviours of this community reflect the patterns constitute in their bequeathed countries of origin [9, 10]. Members of the migrant South Asian customs in the UK, USA and Canada proceed to have a high prevalence of diabetes and coronary heart disease (due to smoking, poor diet, alcohol and depression physical activeness levels), despite comparatively greater admission to healthcare services in their host country [9, eleven] . Currently, 7.four million people in the Britain are living with heart and circulatory illness, where ane in seven men compared to one in 12 women die from coronary center disease (CHD) [12]. Yet, over the past few decades there has been a decline in the mortality associated with CVD in the UK [12]. In improver, a study in Pakistan found that CHD, which is higher amongst men compared to women, contributes to the growing threat of CVD in South Asia [13]. Internationally, lower socio-economic status continues to be detrimental to non-White ethnic groups with regard to their susceptibility to CHD compared to their White counterparts [14]. For example, Pakistanis living in the UK continue to live in areas of greater impecuniousness than their Indian counterparts [xiv] and have bang-up risk for developing CHD (8 and 6% respectively) [fifteen].

In part, this is a reflection of how healthcare campaigns and local policies have failed to incorporate measures to support interaction and integration of migrant, minority-indigenous community members inside preventative healthcare services [16].

Furthermore, health and social policies fail to consider the nuanced socio-cultural and religious differences that influence engagement with healthcare providers and admission to healthcare information [ 17]. As a heterogeneous grouping, there are marked differences in the prevalence of illness and disease within the South Asian diaspora [18]. Compared to Indian men, the risk of CVD, coronary heart disease (CHD), diabetes and associated mortality is higher amongst Pakistani men and they are more than probable to live in some of the near socio-economically deprived areas of the UK, with depression income, poor educational attainment, and continue to face bigotry [xv, 19].

Specifically, mass migration to the UK, from the province of Kashmir in Pakistan during the 1960s, has resulted in a community comprised of first-generation migrants as well every bit a growing young accomplice of second and 3rd-generation descendants who are trying to conform non-traditional, Western practices while balancing acculturation and their migrant status [20]. Often, they alive in inner-city and urban erstwhile industrial areas such as the Due west Midlands in full-bodied settlements i.e. ethnic enclaves [21,22,23].

Social uppercase and migrant wellness

Research has highlighted the importance of social networks and network-based resources in the direction of health conditions and evolution of self-care back up [24]. In terms of migration, contempo migrants can do good from the security that social networks provide and build on existing social capital within microcosms, that can help notice piece of work, housing and support that is non bachelor elsewhere [25]. However, in that location has been contend around the positive 'buffering' effect on health due to living in residential areas with a high ethnic minority concentration [26], that provides protection from racism through increased social Involvement in social networks may be negatively influenced by low socio-economic status that undermines community networks and relationships [27].

In order to better sympathize the socio-cultural factors relevant to these groups and how they influence health behaviours, the theory of social majuscule was applied. The theory of social capital tin can facilitate an understanding of how social networks and resources within an individual's community (concrete and social resources) tin contribute towards shaping wellness beliefs and behaviours. There are several definitions of social capital, but for the purpose of our research, nosotros sympathize social uppercase as "resources embedded in and acquired from social networks and interactions based on connecting ties, trust and reciprocity, through which members of a collective can attain various ends or outcomes that are of benefit for the individual/collective" [25, 27]. At an individual level, social capital provides a puddle of resources from other members of the social network that the individual belongs to [28]. For healthcare, the social network is a tool to access the social capital to obtain information nigh health behaviours, support to undertake lifestyle change (diet or practice) and justify said behaviour [29]. Social networks are structures that tin provide individuals with 'companionship, advice, emotional support and applied assistance' [30].

A review of social capital literature identified a lack of consistency in the operationalisation of social uppercase where migrants, fifty-fifty those having high socio-economical backgrounds, can lack bridging social capital due to limited connections with local people [31]. Within social networks or ties, individuals can form bonds (with like) and bridges (with different) members of the neighbourhood. Networking inside the local neighbourhood can be beneficial; research on social structures within communities in kingdom of the netherlands noted positive associations between neighbourhood-based social upper-case letter and life satisfaction for residents who spend pregnant fourth dimension in their community [32]. A mixed-method study, guided by Bourdieu'south theory of practice, found that the resources necessary to create social upper-case letter (cultural upper-case letter, ability to socially network) differ according to the socio-economic condition of the neighbourhood, but living in affluent areas did not guarantee access to beneficial social networks [33]. Withal, in that location is express enquiry on networking within minority-ethnic groups who are often mobile and have a more than dynamic perception of customs, neighbourhood and social capital [34].

In that location is an assumption that individuals from minority indigenous groups accept the appropriate social or familial back up to manage or forbid wellness weather [35], where a lack of social capital could influence the health inequalities faced past members of the Pakistani community. Links between social upper-case letter and self-intendance are seldom researched in relation to chronic affliction management but could indicate the importance of developing network-centred approaches for engaging socially and economically deprived groups [36]. Research exploring cardiac rehabilitation, concrete activity and CHD in the South Asian customs have uncovered gender based socio-cultural barriers for women, and the role of empowerment, communication, relationships and the environment [37,38,39,40].

Pakistani Muslim men's 'relational, emotional and intimate dimensions' are underexplored. Yet, research past Britton (2019) with Muslim families highlighted the shifting gender and generational relations, in particular, irresolute masculine roles as a event of racism and marginalisation due to socio-political concerns such as 'islamophobia' and stereotyping of Pakistani Muslim men later on incidents such every bit the 'Rotherham grooming' cases [41]. The 'Rotherham child exploitation scandal' consisted of organised kid sexual corruption in the northern English town of Rotherham predominantly by British-Pakistani men and the media framing had an adverse impact on the Muslim community [42]. Pakistani men face social constraints and isolation (similar to other Muslim ethnic minority men who are not Pakistani) inside work environments due to cultural differences resulting in limited networking opportunities. At times, Pakistani men reject mainstream identities especially when living in socio-economically deprived areas ('ghettos') [17, 43].

Within the context of our research, social capital, in item, social networks, are viewed as the mechanisms which Pakistani men can use to achieve their desired health goals. For these men, there are fundamental factors including culturally embedded patriarchy and the generally potent ethos for practising Islam (that can vary between families and individuals) intertwined with the need to maintain certain cultural norms when living in areas of high minority-ethnic density that influence the chances of achieving wellness goals [44, 45].

However, there is insufficient inquiry explicitly exploring social support apropos wellness beliefs and lifestyle choices using an interpretive theoretical lens, especially where the focus is on ane minority ethnic community, such as the Pakistani customs, rather than a mixed-ethnic cohort (Southward Asian).

Method

Aim

We explore migrant Pakistani men's views on health behaviours related to CVD prevention (diet and exercise) and social support for achieving these behaviours inside the local community. Social capital is used as an interpretive lens to understand how social networks, trust and cultural norms can shape Pakistani men'due south access to health data and support a salubrious lifestyle.

Design

A community-based interpretive qualitative written report with in-depth, face-to-face interviews, and completion of the convoy model diagram to help illustrate individual social networks [46].

Setting

Participants were recruited during October 2013–February 2014 from across the West Midlands and in particular Birmingham. Birmingham has the highest concentration of South Asian individuals (13.4% of the total population of Due south Asians living in the UK) compared to other parts of the UK, with the largest non-White grouping being Pakistani (15.4% of minority indigenous groups) [47, 48].

Sampling, access and recruitment

Bug such equally literacy, linguistic communication, translation, knowledge of inquiry, cultural advocacy for taking office in the research (trust and a sense of belonging), obtaining consent, as well as transportation to enquiry facilities were taken into consideration [49]. In the context of our enquiry, ethnic concordance with the researcher encouraged involvement and shared understanding through a shared linguistic communication and socio-cultural background [50,51,52,53].

Participants were recruited using purposive sampling through community businesses that were spatially proximal to members of the Pakistani customs [54]. The concern areas acted every bit enabling places and encouraged participation [55]. We approached a selection of business districts in Birmingham due to their strong ties with members of the local Pakistani community, who acted every bit 'gate-keepers' and 'Research advocates'. For this project, 'Inquiry advocates' were defined equally members of the customs who were willing to promote recruitment and participation through their social connections and build rapport with members of the local customs. Give-and-take-of-oral cavity advertising, third sector organisations, social media (i.due east. Facebook) and snowballing [56] were used in conjunction with the businesses. The report data was presented to participants using 1) data sheets, 2) oral advertisements, three) lay-led posters and 4) informative 'posts' sent through local volunteering services emailing lists.

Participants

Participants' characteristics are outlined in Table i.

Developing the topic guide

Interviews were designed to explore the influence of social networks, trust and cultural norms (as social uppercase) in forming health behaviours related to preventing cardiovascular affliction [57]. The topic guide was piloted with four voluntary participants from the community, who were approached to take function in interviews prior to recruitment for the principal study, to explore its strengths and weaknesses and the ability to translate questions into Urdu (the linguistic communication predominantly spoken in Pakistan) [58]. Equally a response to feedback from participants, the topic guide was further developed to avert dichotomous responses in Urdu as some questions became shut-concluded when translated. Consequently, the piloted topic guide included components of the social majuscule theory including social networks, trust and cultural norms with changes that better suited the nature of this investigation every bit it 'outlined key issues and subtopics to be explored with the participants' [59]. A copy of the interview guide can exist provided upon asking.

Data collection

Participants were invited to accept part in a 1-to-1 interview that would last an hour in a location of their choice (home, work, business organisation place they were recruited from, or at the University) and in their preferred language (English language, Urdu or Punjabi). The interview process involved introducing the written report (verbally and/or giving an information canvass, in Urdu or English), completing the Convoy model diagram [lx], and the interview. The Convoy model proposed by Kahn and Antonucci (1980) is a framework for observing social network development over time [60]. The diagram consists of a series of concentric circles, with the individual at the centre and the importance and proximity decreasing with each progressing circle. Participants were asked to write their name in the heart of their circles and and so place the names of individuals (e.k. mother or sister) based on the importance of that human relationship. The names of relationships were placed on one of three circles, where the commencement innermost circle was for the most of import relationships, and with each progressing circumvolve the relationships became less important. Although, the Convoy model was designed to collect data on the effects of ageing on social networks, it has been applied to other contexts such as accessing health data and back up [61]. The diagram has also been used to explore components of social capital to understand ameliorate the human relationship between social networks, across age (younger and older), socioeconomic status and lifestyle choices [40, 62]. Our purpose was to elicit a personalised illustration of human relationship networks, achieve conceptual equivalence (same understanding of a concept in all languages) of different terms (e.thou. social networks) and use it to elicit discussions on social relationships and trust. The model was used purely to elicit word on social networks, irrespective of participant age. At times participants referred to websites and images on their phones to illustrate their points (without prompt).

Ethics

All data were stored in accord with University of Birmingham upstanding guidelines. Ethical approval was given past The Academy of Birmingham Science, Technology, Technology, and Mathematics Ethical Review Commission application number: ERN_13–0450. All participants provided written consent to take part in the research and were informed of their right to withdraw.

Analysis

Data collection was an on-going and iterative process where transcribing and coding occurred simultaneously until saturation was reached [63].

The interviews were carried out between October 2013 and February 2014, sound-taped on encrypted recorders, transcribed verbatim (also as anonymised), and where necessary translated into English (by FK and checked past MS and PG) [64, 65]. NVivo xi software was used to manage the data during assay. A South Asian researcher based at the University of Birmingham verified samples of the transcripts for conceptual equivalence, and to ensure accuracy and quality of translated material.

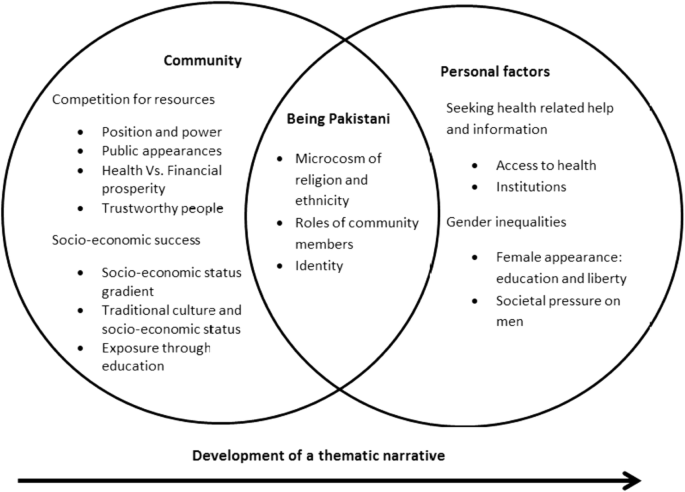

The framework method was used to provide a transparent outline of the analysis based on typologies (historic period, gender and generation), concepts, and differences and similarities [66]. The researchers worked through v stages of analysis: 1) familiarisation with the data, ii) identification of a thematic framework, 3) indexing (systematic application of the coding framework), 4) charting (creating charts with participant demographics and data), and five) mapping and estimation [67]. Data reduction was achieved by systematically placing the information into manageable charts as a process of data management and reduction [68]. The major themes were used to categorise the frameworks as functional categories. Figure ane illustrates the development of themes into categories.

Development of the thematic narrative (communal to personal perspective)

Results

The views of 21 tri-generational men from dissimilar educational and occupational backgrounds were analysed to sympathise men's perceptions of social networks and admission to health support from the Pakistani migrant customs across the West Midlands, UK. An outline of the dissimilar areas of the West Midlands participants were recruited from is given in Table 2.

Findings of this research will be presented by illustrating participants' views of their local surface area every bit a Pakistani microcosm and ethnic enclave, with ii prominent social spaces of influence: The Mosque and the gym. Perceptions and pluralism centred effectually identity only were as well generationally interpreted. Although all participants identified every bit Pakistani, self-perception was also nuanced along the lines of contrasts between Pakistani, Eastern norms with British and Western culture throughout the themes, where at times participants identified themselves as British Pakistanis and the internal conflict this brings.

Pakistani microcosm

Pakistani microcosms in U.k. can be singled-out in terms of their 'rules, standards, organized religion, community, economy, and reality' [73]. Within our research, participants noted how their local surround played an essential part in reinforcing traditional Pakistani norms and forming identities. The first-generation participants' narratives centred around identity and perceptions, which shed calorie-free on generational divisions.

For example;

"I used to think that in one case the first-generation immigrants have washed their time, the side by side generation will be better, only unfortunately I meet they are actually worse, because, their living style is different, they look distinctly different, if you lot wait at them and their manner of, the beard and all that in that location'southward single line running from at that place and there (gesturing to face up), yous don't see that in anybody else so its specific to Asian young men, the wait they take. They speak different, it'south not a, a proper language...its slang lingo which they use"

(fifty+ years, first-generation, IMD 3, area B)

"The about important matter in Pakistani culture is that women have to be covered. So, nigh sports women are not fully covered, so that is a big decision for the family to take. Then as long as the woman who is playing, if she is playing some sport and she is fully covered then I recall she should exist allowed to play"

(18–29 years, first-generation, IMD 5, area E)

One of the participants further provided insight into how information technology is possible to amend navigate any tensions by all-around Western and Eastern norms alongside each other while reflecting positively on successful acculturation into the UK.

"So, integration has never been an issue: we accept maintained the expert qualities of our cultural background. Nosotros have adopted lots of very, very good things, which is in this culture (British). So, I would say that is a hybrid"

(50+ years, kickoff-generation, IMD three, expanse B)

Political and socio-spatial aspects of living in a majority migrant environment afflicted the development of individual identities, where living in an area with high ethnic-density (i.e. that participants described as a social globe defined by 'Pakistani' values) increased exposure to influences strengthening the borough notions of being Pakistani. Despite any perceived sense of security associated with living in a predominantly Pakistani area, some 2d-generation men felt their parents' decision to live in such areas limited exposure to other communities, cultures and social practices.

"The thing they (parents) lacked were mixing, living in the English lifestyle 'cos they weren't taught to exercise that and bringing upward their children, English children. You can't be a Pakistani from Pakistan; your children have to exist brought up similar the British"

(30–49 years, second-generation, IMD iv, area H)

Limited integration was viewed as a disadvantage by some participants, apropos their social development, equally they vocalised the effects of express integration and understanding of British lifestyle choices due to participants' concerns over losing their migrant cultural-religious identity [74].

Social mobility and traditional values

Whereas commencement-generation men were preoccupied with labour intensive jobs and settlement, 2nd-generation customs members justified their need to be competitive and fulfil their aspirations to develop beyond their 'migrant' condition and bear witness trans-generational growth, eastward.g. by challenging stereotypical views of unhealthy and overweight Pakistani men.

"They've had their kids, they've bought their backdrop, they're brought their belongings in Pakistan; they've done enough at present. I don't recall they strive to alive to 90 years or 100 years. I think they alive to 70 and lxxx years and and then they're happy and that's the difference"

(30-49 years, second-generation, IMD 4, expanse H)

Community members were witting of diffusive from the traditional extended family model and associated norms by aiming to increase monetary capital and accessing diverse social networks. This could cause tensions between first- and second-generation men every bit lifestyle choices seen every bit 'modernistic' behaviours were associated with socio-economical success and a disregard for family values.

"Y'all'll have the secular types, the families who are very professional person, who are, you know, earning forty-50k a twelvemonth, his married woman will exist professional as well, I don't think they will be, [don't] practise too much looking later their elders, personally, ones with traditional values, yes! Merely certainly, mod values, no"

(30–49 years, second-generation, IMD 5, area B)

Up social mobility towards new spaces and away from community norms in ethnic enclaves was viewed every bit an opportunity to limit exposure to unhealthy lifestyle choices. Living or existence close to takeaways could atomic number 82 to excessive calorie intake and limited physical activity in lower-income and deprived communities [75].

"Go to (location Site A) and that's seen as upper class. So, you will not discover a takeaway for a practiced stretch of a mile or two. Naturally, more than probable than not, considering of their daily routine, most of the people working there are working 9-v, 9-half-dozen. So, virtually of their food is self-prepared, right, whereas our food, well, if we don't like it, you've got a chip shop right just there, gear up-made for you … but what's nowadays in the community is having an influence on your health" (18–29 years, second-generation, IMD five, area E)

The limited socio-economic evolution of some members of the Pakistani community was further demonstrated in the ability of younger generations to afford to adjust their diet to suit their physical lifestyles. The narratives of moving away are intertwined with creating distance from cultural pressures and opening up to more than diverse networks. At times, 2nd-generation men chose not-traditional meals and routines to achieve their personal goals of looking masculine. The aforementioned quote as well illuminates the disparity between participants from lower and more center socio-economic status backgrounds. Participants who were adopting more than middle-class values were moving away from local spaces and traditional migrant behavior, whereas younger, working class participants were taking more ownership over spaces and trying to change the meanings, values, and beliefs in deprived communities whilst trying to efficiently utilise their existing social networks to improve their lifestyles. Every bit some participants were recruited from areas with high levels of impecuniousness, it was apparent that income and occupation was associated with admission to food options and related to lifestyle patterns.

Wellness and social needs of first-generation men

Health spaces where members of the community can obtain healthcare and lifestyle knowledge or information (e.k. on diet and exercise) are age and generation-centric based on the different needs of older, younger and recently arrived migrant men. When outlining the primal institutions that played a role in their physical, emotional and social well-being, Pakistani men noted the General Practitioner'south (GP) surgery as an important source of information for first-generation men.

Generational differences were also reflected in the health-seeking behaviour of starting time-generation and older migrant participants who relied on the information provided by their GPs; particularly when seeking balls.

"The dr. that I know he treats me very well, he gives me medicines, annihilation that I need to get I go far a prissy manner"

(50+ years, first-generation, IMD 5, area B)

Second-generation men did not share these views and were more than dissatisfied by the approach used past their GP, resulting in them relying on alternative sources of information; predominately, online resources and through social networks.

"I recollect going to the gym has been a big contributing factor with that because you encounter other individuals who you lot see, they've achieved good physical shape and you enquire them for tips. You go online y'all do inquiry, and plain they but practise that at piece of work, in a lot of things that I've learned through academia fabricated me aware of what things I need to look out for, what diseases there are out in that location and how they develop. So, I call back, obviously self-education is primal but all that comes through participating in these kind of activities, i.e. going to the gym, playing sports and, that'southward how you run across things"

(18–29 years, 2d-generation, IMD 5, area I)

For some starting time-generation and older men, it was recognised that the Mosque, rather than the local gym, promoted integration within the community.

"Infant steps, Rome wasn't congenital in a solar day … information technology's about investing that time in individuals not as cattle or herd, do you know who's got a big role to play in all this? Our ain community, you and I know that the public services and strategy organisations aren't funding, and sources are very express, our Mosques and our Gurdwaras our Hindu temples have got a big function to play in this"

(thirty–49 twelvemonth, second-generation, IMD 5, area B)

Although, at times, Pakistani men of different ages and generations may be using the same health infinite, what is considered a health infinite or not differs. For case, for older men, the Mosque was considered a location for promoting dialogue and raising awareness surrounding community well-being and health.

Ethnic enclaves and Pakistani patriarchy

First- and second-generation participants commented on the high level of perceived security threats inside (inter-familial conflicts) and outside (discrimination) of their community as a motivation for monitoring and controlling women'south behaviour. By sensationalising stories of women beingness harmed in the wider community, men could emphasise the demand for their authority and vigilance.

"My sister was racially attacked, years ago. My elder sis, she used to embrace (hijab) and some Blackness guys attacked her. She phoned me; I didn't go there in time, but my friends did though"

(30–49 years, 2nd-generation, IMD 4, area H)

Masculinity within the context of British Pakistanis' lives was reinforced in men's attitudes towards women. Men felt a degree of responsibleness in determining the level of safety in the local surface area for women to socialise or exercise in. Prophylactic meant protection from physical but also ideological threats through limiting exposure to unfamiliar or novel lifestyle practices. These views also included gender perceptions, where women are expected to remain slim in maidenhood to successfully obtain a suitable spouse.

"There'southward more than pressure on girls and I retrieve that'southward what causes them to be more health conscious. I'thousand not proverb its proficient force per unit area, but that is one of the ways, 'cos unfortunately, society, you know … a girl gains a bit of weight she's seen as unattractive or whatever, whereas a guy, even with a scrap of weight if he'southward doing alright (financially) in life, he'due south very much attractive" (18–29 years, second-generation, IMD 5, area I)

Men recognised the barriers that were placed on women and the express opportunities that were offered to them. Younger men may not actively enforce patriarchal values but recognise the role they play to inhibit women'due south health and well-beingness while supporting men within the customs.

"… it's hard for the community to see women go to the gym, I think they're just expected to non actually concentrate on their wellness much. In some cases, guys get nutrient cooked for them from the family (if) they want to become to the gym and work out, but if that was a girl, I don't call up that would be the same case"

(18–29 years, second-generation, IMD 5, expanse Due east)

Living in a detail area further perpetuated sure expectations and gender-based roles that were difficult to negate.

Young men'southward territory

Second-generation men and the gym

Younger men preferred the gym every bit a social infinite, which they viewed as a machinery for developing their status within the community (every bit providers, leaders, and protectors), access to social networks and develop physical strength, where health was not necessarily the main concern just a secondary outcome.

"I don't call back they do it for health reasons because they're- people wanna go to the gym and they can do it simply- they want to do it, to look good in a t-shirt"

(18–29 years, second-generation, IMD four, expanse H)

This participant notes that the gym provided individuals with the opportunity to shape their physique, to wait a item manner for social gratification. Consequently, some men were territorial about their workout infinite, which they deemed unsuitable for older men and in particular women.

"If she takes that first footstep, she goes in, and there's a lot of sweaty guys grooming, making all sorts of noises, information technology's uncomfortable. Whereas, if you went to (brand gym), it's normal to have people of all ranges and ages and colour … whereas you come in to my gym and yous come across fat, hairy guys, and yous're sweating 'argh' (grunting noises), the girls are not gonna want to be in that location …"

(xviii–29 years, male, second-generation, IMD 5, area E)

This participant's views on the gym encapsulate community sentiments on gender and generational differences on how individuals socialise within socially segregated spaces. The gym is a space designated for immature men to shape their bodies simply also develop their thinking towards social matters and issues. The nature and level of support available within the wellness space were targeted at young Pakistani men to develop their social capital past forming connections with others from a similar age and generation; who shared their experiences of growing up in a British Pakistani community and its encompassing cultural norms.

Again, territorial views on 'Asian gyms' every bit spaces that facilitated Pakistani men's social and physical goals contribute to the dialogue on socially segregated spaces and how they can shape contemporary cultural norms:

"If you lot go to a White persons' gym, everything is in the aforementioned room, if you go to an Asian human'south gym y'all've got weights and weights and weights, and you'll have a little room in the corner … it'll have similar three treadmills"

(18–29 years, second-generation, IMD 5, area E)

Working out in local gyms in comparison to branded facilities likewise aligned with the formation of identity as i of the local 'meatheads', perceptions of socio-economic status (men working hard to appear physically strong despite their socio-economical status) and perceived level of acceptance. This reflects more traditional Pakistani or Indian Panjabi perceptions of masculinity based on physical forcefulness [52]. Some participants felt more comfortable focusing on developing a muscular physique in the local gym rather than the more than holistic approaches adapted by bigger brands.

"'Meatheads' pregnant the big bulky guys who actually, more of a guy's gym rather than the normal health club that y'all'd expect, similar women or stuff like that. They wouldn't be there. Information technology's unremarkably a guy'southward gym"

(18–29 years, third-generation, IMD 5, surface area East)

Consequently, some participants who could beget to avoid these wellness-related spaces described their discomfort with them;

"I just didn't feel skilful in that surroundings. Like, there was a lot of people, the fashion they just talked to each other, at that place was a lot of bad words existence said, and you could sometimes smell them doing drugs or, it just wasn't a prissy environment"

(18–29 years, 2d-generation, IMD 5, surface area E)

Physical and moral forcefulness

The gym was an arena where men shared their knowledge and experiences on how to stay fit and continue being exemplary, young Pakistani men. It became apparent that the use of their local gym as a source of inspiration, socialisation, and contest for a masculine physique contributed to the desire to be an affluent member of the community equally reflected in the rivalry participants expressed in terms of their physical appearance (demonstrating masculine force and morals). Men with a larger and stronger, socially desirable alpha-male person physique were seen as role models and meliorate suited to hold positions of authority or leadership in their family or community.

"I've got the broad shoulders to make decisions, whether the family likes them or not, and that's the office I play in my family unit"

(30–49 years, second-generation, IMD iv, expanse H)

Men developing their physical strength was a demonstration of their delivery to protecting their family unit and their customs's cultural values and norms. In some instances, protecting (defending) the cultural norms of the customs was taken literally.

"The weaker y'all are the more vulnerable you are to other people, the more prone y'all are to being attacked, then the more healthy y'all are you can protect yourself, you lot tin protect your family unit, if y'all go into a fight or something and you lot are weak, its most likely that the person that's fighting you will be stronger than y'all … protection, protecting yourself, protecting your women, protecting your children, I remember that is a big motivation (for going to the gym or existence healthy)"

(18-29 years, beginning-generation, IMD 5, expanse E)

Despite their perceived status as protectors, Pakistani men could not borrow upon the 'tight' (established) cultural norms in the customs that dictated social or personal behaviour. Consequently, 'deviant' or haram behaviour could negatively touch on an private's position within their customs networks and competition to remaining in a superior authoritative (masculine) role. The desire to be an influential (physically and morally) figurehead required a balance between adopting Western behaviours (going to the gym and culling diet) and a vigilant moral compass (against behaviours that challenge the community'southward norms). Pakistani men were self-conscious of how quickly they could come up under scrutiny from one another in this rivalry for leadership.

"The younger generation at the moment is hot headed, and one time, if they encounter yous in expert shape or that you take a good body, they get jealous, similar, 'look at him, he has a good body, we don't' and even an statement tin can start over a trivial matter"

(18–29 years, first-generation, IMD 5, area E)

Interviewees felt that immature men competed with each other for a stronger physique, and not but to exert their power and dominance (control) over their family members (related to being their protector).

Discussion

Our written report shows how second-generation Pakistanis in pursuit of professional careers or higher teaching were more likely to be exposed to various groups of people, and consequently accept greater exposure to culling lifestyle choices and opportunities to seek out healthcare information and support. Nevertheless, 2nd-generation descendants of migrants continued to experience disadvantaged in their ability to admission potential networks of data and support due to the disparity between their experiences and that of the wider population, especially if their parents are migrants and/or speak a foreign language at home [76]. These patterns of behaviour amidst second or 3rd-generation community members are not unique to the Pakistani community, as generational shifts are common amongst migrants when negotiating cultural or religious ambiguity amid other indigenous communities. Generational differences practice not only have the potential to influence shifts in cultural norms but can also bear upon appointment and citizenship where alternative social and political opportunities are available [77]. For example, second-generation Swedish-Sikh immigrants have struggled with dissimilar arenas of power (religious, traditional and cultural) to adopt religious norms and individual interpretations into networking opportunities within their wider social networks, eastward.g. cocky-assist activities for the youth at the Gurdwara that contain contemporary issues inside a traditional setting [78].

Our findings contribute to the current understanding of the role of social motivators (such equally contest for an alpha-male position) in the Pakistani community e.thousand. when going to the gym and moving beyond the pursuit of better physical health towards appearance in the community [79]. Virtually notably, Pakistani men viewed their local gyms (that were run by other Pakistani men in the community) every bit the ideal location to socialise within and familiarise themselves with the community's norms. The role the gym played as a social space for men to define their masculinity can exist linked to how perceptions of masculinity are associated with traditional masculine behaviours, such as health benefits and a stronger gender identity to accumulate 'masculine capital' [80]. 'Masculine capital' incorporates the skill sets and cultural competence required for men to fulfil social expectations in society [81]. 2nd-generation men dominated their social networks through their display of physical strength; stronger men were more likely to be approached for advice and back up because their size was an indicator of i) access to wider customs resources e.g. the gym, ii) being able to afford an expensive, high protein diet, and iii) having knowledge of health benefits i.east. nutrition and exercise techniques.

The gym was clearly marked equally a male person wellness infinite. Men used social spaces to define socio-culturally and religiously advisable behaviours for women in their families. The bear upon of strong 'hegemonic masculinity' inside the home during a reject in professional condition at work has been noted [81], where the role of race, ethnicity and socio-cultural influences touch the formation of masculine identities [82, 83]. Making an association between 'Asian'/Pakistani/'meathead' gyms to masculinity and being working form was contrasted with the 'brand' gyms for White men, women and a focus on health rather than appearance as a style of reinforcing their masculinity and control over their environment. Men from minority communities acquire say-so through responsibility and concrete forcefulness, which may pb to subordinating women in the community [84]. Expectations for women were non express to the apply of social spaces but included women's concrete and moral appearance. Women were expected to exercise in their homes, dress modestly when in community spaces (to preserve cultural values), compared to men who can socialise exterior of the familial vacuum. This behaviour created a hierarchy in the community, where greater agency is given to men for how women should carry and how to influence the local community spaces to reflect this.

Existence in close proximity to like others, participants felt they were constantly critiquing each other concerning culturally acceptable behaviours. Every bit members of the Pakistani customs tend to live in areas with a high concentration of ethnic minorities and polarised enclaves, there is a higher tendency for conflicts to arise [85,86,87]. This course of 'ghettoization'/segregation can adversely affect the lived experience within communities, with limited social capital and exposure to wider customs settings [88].

Limitations

Our findings present a 'snapshot', of Pakistani men living in the West Midlands, UK. How local health facilities are accessed or cater to for male person health trends in the Pakistani community, should not exist generalised to a wider population. Yet, findings may exist transferable to other BAME groups. The nowadays research provides insight into a migrant community in Britain, which may be transferable to other migrant populations in high-income-countries. A further limitation of the study was the inability to incorporate the multi-media data shared by participants (provided with no prompt) in order to protect their identity. Participants illustrated their experiences and described their social networks using photographs and websites in a bid to help the interviewer sympathise their lifestyle choices. Further research incorporating images to elicit responses and develop dialogue, using 'Photovoice' or 'photo-elicitation' methods, may be beneficial [89, xc]. Additionally, a greater attempt should be made to include tertiary-generation participants due to their limited representation in research generally.

A reflexive arroyo was taken to consider the influence of a female interviewer completing interviews with Pakistani men. The multi-disciplinary research team (consisting of men and women from psychology, medical folklore, and clinical backgrounds, and of Due south Asian, British and European descent) contributed to the analysis and interpretation of the findings to minimise bias. Information collection was undertaken until saturation [91].

Implications for health (promotion/practice)

Recommendations can be made for improve integration between main and community intendance, and the uptake of health services around lifestyle changes in not-traditional health settings. Healthcare providers tin can adopt greater sensitivity towards socio-cultural barriers that are faced by migrant community members while trying to incorporate an agreement of personal identity and lifestyle choices [53]. Acculturation amidst 2nd or 3rd-generation migrants may vary and bear upon their employ of community and online health resources, whereby recommended (e.g. NHS) websites can be promoted [92]. Furthermore, an overall holistic approach to healthcare that involves family members and locally recruited staff may develop social capital among community members, reduce isolation and increment confidence to make healthier lifestyle choices [93, 94]. The Mosque and gym are community spaces that can be involved in health outreach activities and should be considered when designing interventions or public wellness campaigns that seek to engage with different members of the community; especially get-go-generation or younger Pakistani men.

Decision

Religion centred locations, such as Mosques, are prestigious social institutions that provide an opportunity to address some of the issues surrounding support and cognition; however, not all community members (such as younger, 2d-generation men or women) experience this is currently appropriate. An effort to develop centres or advocates to promote alternative, culturally advisable lifestyle choices could support the pursuit of a healthier lifestyle beyond diverse migrant community populations while encouraging social date. Nevertheless, at that place is a hierarchy of socio-cultural factors that influence the formation of lifestyle choices, where health may non be a priority and trust is required to build novel support networks.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets generated and analysed during the electric current report are not publicly available due to concerns over anonymity and confidentiality, simply some information is bachelor from the corresponding writer on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- BAME:

-

Black and minority ethnic

- CVD:

-

Cardiovascular disease

- CHD:

-

Coronary heart disease

- GP:

-

Full general practitioner

- NHS:

-

National Health Service

- United kingdom:

-

Uk

- USA:

-

The states

References

-

Bhupathiraju SN, Hu FB. Epidemiology of obesity and diabetes and their cardiovascular complications. Circ Res. 2016;118(11):1723–35.

-

Langellier BA, Garza JR, Glik D, Prelip ML, Brookmeyer R, Roberts CK, Peters A, Ortega AN. Immigration disparities in cardiovascular disease hazard gene sensation. J Immigr Small-scale Health. 2012;14(6):918–25.

-

The NHS. The NHS longterm plan. London: NHS; 2019.

-

Evans H, Cadet D. Tackling multiple unhealthy risk factors: emerging lessons from practise. London: The King'south Fund; 2018.

-

Macintyre S. The patterning of health by social position in contemporary United kingdom: directions for sociological research. Soc Sci Med. 1986;23(4):393–415.

-

Becares 50, Nazroo J, Albor C, et al. Examining the differential clan between self-rated wellness and area deprivation among white British and indigenous minority people in England. Soc Sci Med. 2012;74(4):616–24.

-

Roe J, Aspinall PA, Thompson CW. Understanding relationships between wellness, ethnicity, place and the role of urban green infinite in deprived urban communities. Environ Res Public Health. 2016;13(681). https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph13070681.

-

Office for National statistics. (2013). KS201UK Ethnic group, local authorities in the United Kingdom. Available: https://www.ons.gov.britain/peoplepopulationandcommunity/populationandmigration/populationestimates/datasets/2011censuskeystatisticsandquickstatisticsforlocalauthoritiesintheunitedkingdompart1. Last Accessed xvi/04/2019.

-

Agarwal SK, Lovell A. High-income Indian immigrants to Canada. South Asian Diaspora. 2010;2(2):143–63.

-

Holmboe-Ottesen G, Wandel M. Changes in dietary habits subsequently migration and consequences for health: a focus on southward Asians in Europe. Food Nutr Res. 2012;56(10). https://doi.org/x.3402/fnr.v56i0.18891.

-

Lucas, A; Murray, E; Kinra, S (2013) Heath beliefs of Great britain south Asians related to lifestyle diseases: a review of qualitative literature. J Obes, 2013. p. 827674. ISSN 2090-0708 doi:https://doi.org/x.1155/2013/827674.

-

British Heart Foundation. Great britain Factsheet. London: BHF; 2020.

-

Gaziano TA, Bitton A, Anand S, Abrahams-Geisel S, Murphy A. Growing epidemic of coronary heart disease in low- and middle-income countries. Curr Probl Cardiol. 2010;35(2):72–115.

-

Bhopal RS, Hayes L, White Thousand. Indigenous and socio-economic inequalities in coronary heart affliction, diabetes and take chances factors in Europeans and south Asians. J Public Wellness Med. 2002. https://doi.org/x.1093/pubmed/24.2.95.

-

Scarborough P, Bhatnagar P, Kaur A, Smolina K, Wickramasinghe Thousand, Rayner M. Ethnic differences in cardiovascular disease, 2010. Department of Public Health, University of Oxford. Oxford: British Heart Foundation; 2010.

-

Liu J, Davidson East, Bhopal RS, et al. Adapting wellness promotion interventions to meet the needs of ethnic minority groups: mixed-methods evidence synthesis. Wellness Technol Needs Appraise NIHR HTA Programme. 2012;16(44):1–469.

-

Kokab F, Greenfield Due south, Lindenmeyer A, Sidhu Thou, Tait L, Gill P. The experience and influence of social support and social dynamics on cardiovascular disease prevention in migrant Pakistani communities: A qualitative synthesis. Patient Educ Couns. 2018;101(4):619–xxx.

-

Banerjee AT, Shah BR. Differences in prevalence of diabetes among immigrants to Canada from s Asian countries. Diabet Med. 2018;35(7):937–43.

-

Tackey ND, Barnes H, Khambhaita P. Poverty, ethnicity and education. York: JRF programme paper: Poverty and ethnicity; 2011.

-

Din I. The new British: the touch on of culture and customs on young Pakistanis. Hampshire: Ashgate; 2016.

-

Werbner P. Manchester Pakistanis: division and unity. In: Clarke C, Peach C, Vertovec S, editors. Southward Asians overseas: migration and ethnicity. New York: Cambridge University Printing; 1990. p. 331.

-

Ali N, Kalra VS, Sayyid S. A postcolonial people: South Asians in United kingdom. 1st ed. Bharat: C. Hurst & Co (Publishers) Ltd; 2006.

-

Werbner P. Pakistani migration and diaspora religious politics in a global age. In: Ember One thousand, Ember CR, Skoggard I, editors. Encyclopaedia of diasporas: immigrant and refugee cultures effectually the earth. New York: Springer; 2005. p. 475–84.

-

Rogers A, Vassilev I, Sanders C, Kirk S, Chew-Graham C, Kennedy A, Protheroe J, Bower P, Blickem C, Reeves D, Kapadia D, Brooks H, Fullwood C, Richardson G. Social networks, work and network-based resources for the management of long- term conditions: a framework and study protocols for developing self-care support. Implement Sci. 2011;29(half dozen):56.

-

Hyyppa MT. Healthy ties: social upper-case letter, population health and survival. Netherlands: Springer; 2010.

-

Becares 50, Nazroo J. Social capital, ethnic density and mental health among ethnic minority people in England: a mixed-methods report. Ethn Wellness. 2013;18(6):544–62.

-

Robison LJ, Schmid AA, Siles ME. Is social uppercase actually capital? Rev Soc Econ. 2002;lx(i):1–21.

-

Ellison NB, Steinfield C, Lampe C. (1). The benefits of Facebook "Friends": Social Capital and college students' use of online social network sites. J Comput Mediat Commun. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1083-6101.2007.00367.10.

-

Wilkinson R, Marmot 1000. Social determinants of wellness: the solid facts. 2nd ed. Denmark: World Wellness Organisation; 2003.

-

Gottlieb BH, Sylvestre JC. Social support in the human relationship between older adolescents and adults. In: Hurrelmann G, Hamilton SF, editors. Social issues and social contexts in adolescence: perspectives across boundaries. New York: Transaction Publishers; 1996. p. 153.

-

Villalonga-Olives E, Kawachi I. The measurement of bridging social capital in population health research. Wellness Place. 2015;36:47–56.

-

Hoogerbrugge MM, Burger MJ. Neighborhood-based social capital and life satisfaction: the case of Rotterdam, kingdom of the netherlands. Urban Geogr. 2018;39(10):1484–509.

-

Browne-Yung ZA, Baum F. 'Faking til you make it': social capital accumulation of individuals on low incomes living in contrasting socio-economic neighbourhoods and its implications for health and wellbeing. Soc Sci Med. 2013;85:9–17.

-

D'Addario S, Hiebert D, Sherrell K. Restricted access: the office of social capital in mitigating absolute homelessness among immigrants and refugees in the GVRD. Urban Refuge. 2007;24(1):107–15. https://doi.org/x.25071/1920-7336.21372.

-

Katbamna Southward, Ahmad Due west, Bhakta P, Baker R, Parker One thousand. Do they await after their own? Breezy support for south Asian carers. Health Soc Care Community. 2004;12(five):398–406.

-

Vassilev I, Rogers A, Sanders C, et al. Social networks, social capital letter and chronic affliction self-management: a realist review. Chronic Illn. 2011;seven(i):60–86.

-

Galdas PM, Ratner PA, Oliffe JL. A narrative review of south Asian patients' experiences of cardiac rehabilitation. J Clin Nurs. 2012;21(1–2):149–59.

-

Fischbacher C, Hunt Due south, Alexander Fifty. How physically active are south Asians in the United Kingdom? A literature review. J Public Wellness. 2004;26:250–8.

-

Daniel M, Wilbur J. Physical activity among s Asian Indian immigrants: an integrative review. Public Wellness Nurs. 2011;28(v):389–401.

-

Horne M, Tierney S. What are the barriers and facilitators to exercise and physical activity uptake and adherence among s Asian older adults: A systematic review of qualitative studies. Prev Med. 2012;55(4):276–84.

-

Britton J. Muslim men, racialised masculinities and personal life. Folklore. 2019;53(1):36–51.

-

Tufail W. Media, state and 'political correctness': the racialisation of the Rotherham child sexual abuse scandal. In: Bhatia Thou, Poynting S, Tufail West, editors. Media, crime and racism. Palgrave studies in crime, media and culture. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan; 2018.

-

Maxwell R. Muslims, south Asians and the British mainstream: a national identity crisis? West Eur Polit. 2006;29(4):736–56.

-

Dhami South, Sheikh A. The Muslim family: predicament and promise. West J Med. 2000;173(5):352–half-dozen.

-

Predelli LN. Interpreting gender in Islam: A case report of immigrant Muslim women in Oslo, Norway. Gend Soc. 2004;18(four):473–93.

-

Antonucci TC, Akiyama H. Social networks in adult life and a preliminary examination of the convoy model. J Gerontol. 1987;42(5):519–27.

-

Office for National Statistics (2011) Ethnicity facts and figures, Available at: https://www.ethnicity-facts-figures.service.gov.united kingdom of great britain and northern ireland/british-population/demographics/people-born-outside-the-great britain/latest Accessed eight Feb 2019.

-

Birmingham City Council, Demography 2011 population and migration profile for wards and constituencies in Birmingham, Available at: https://www.birmingham.gov.uk/downloads/file/4616/census_2011_population_profile_for_small_areas_in_birminghamxls. Accessed 12/09/xix.

-

Hussain-Gambles Chiliad, Atkin Yard, Leese B. South Asian participation in clinical trials: the views of lay people and health professionals. Health Policy. 2006;77(2):149–65.

-

Prevarication MLS. Methodological issues in qualitative research with minority ethnic inquiry participants. Res Policy Plan. 2006;24(2):91–103 Cortazzi et al 2011.

-

Ahmed F, Abrl GA, Lloyd CE, Burt J, Roland M. Does the availability of a due south Asian linguistic communication in practices improve reports of doctor-patient communication from south Asian patients? Cross sectional analysis of a national patient survey in English general practices. BMC Fam Pract. 2015;16(55):1–12.

-

Sidhu G, Kokab F, Jolly K, Marshall T, Gale NK, Gill P. Methodological challenges to cross-linguistic communication qualitative enquiry with south Asian communities living in the UK. Fam Med Community Health. 2016;three(three).

-

Palinkas LA, Horwitz SM, Green CA, Wisdom JP, Duan North, Hoagwood K. Purposeful sampling for qualitative information collection and assay in mixed method implementation inquiry. Admin Politico Ment Health. 2015;42(5):533–44.

-

Soldatic K, Morgan H, Roulstone A. Disability, spaces and places of policy exclusion. Oxon and New York: Routledge; 2014.

-

Browne Thousand. Snowball sampling: using social networks to research not-heterosexual women. Int J Soc Res Methodol. 2003;8(one):47–60.

-

Lin Due north. Social capital: A theory of social structure and action. New York: Cambridge University Press; 2001.

-

Ayres A. Speaking like a land: language and nationalism in Islamic republic of pakistan. UK: Cambridge University Press; 2009.

-

Arthur, S., Mitchell, M., Lewis, J. and Nicholls, C. M (2014) 'Designing fieldwork', in Ritchie J, Lewis J, Nicholls CM and Ormston (ed.) Qualitative inquiry exercise: A guide for social scientific discipline students and researchers. London, New Delhi, Singapore: Sage Publications, pp. 149.

-

Antonucci TC, Ajrouch KJ, Birtditt KS. The convoy model: explaining social relations from a multidisciplinary perspective. Gerontologist. 2014;54(i):82–92.

-

Ajrouch, G.J., Blandon, A. Y and Antonucci (2005) 'Social networks among men and women: the furnishings of age and socioeconomic status', J Gerontol, 60B (half-dozen), pp. 311–317.

-

Fingerman KL, Berg CA, Smith J, et al. Handbook of life-span evolution. New York: Springer Publishing Visitor. LLC; 2011.

-

Levitt MJ, Guacci-Franco N, Levitt JL. Social back up and achievement in babyhood and early on adolescence: A multicultural study. J Appl Dev Psychol. 1994;15(ii):207–22.

-

Tesch R. Qualitative research: analysis types and software tools. London: Psychology Press; 1990.

-

Papadopoulos I. Culturally competent research: a model for its evolution. In: Nazroo JY, editor. Health and social enquiry in multiethnic societies. London and New York: Routledge; 2006. p. ninety.

-

Ritchie J, Spencer L. Qualitative data analysis for applied policy enquiry. In: Bryman A, editor. Analyzing qualitative data. London and New York: Routledge; 1994. p. 305.

-

Tilling K, Peters T, Sterne J. Key issues in the statistical assay of quantitative information in enquiry on wellness and health services. In: Ebrahim Due south, Bowling A, editors. Handbook of wellness enquiry methods: investigation, measurement and analysis. Berkshire: Open Academy Press; 2005. p. 522.

-

Gale NK, Heath G, Cameron E, Rashid S, Redwood South. Using the framework method for the analysis of qualitative data in multi-disciplinary wellness inquiry. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2013;thirteen(117):i–eight.

-

Steele E. Interdisciplinarity, multidisciplinarity and transdisciplinarity in humanities. Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing; 2016.

-

Iqbal K. Love Birmingham: a chat with my hometown. U.s.: Xlibris Corporation; 2013.

-

Sandwell trends. 'Smethwick 2011 Census Town Profile' [Online]. 2013. Available at: world wide web.sandwelltrends.info/lisv2/navigation/download.asp? ID=721. Accessed February 2016.

-

Birmingham City Quango (2014) Demography information: population and census, Available at: http://www.birmingham.gov.uk/cs/Satellite?c=Page&childpagename=Planning-and-Regeneration%2FPageLayout&cid=1223408069551&pagename=BCC%2FCommon%2FWrapper%2FWrapper. Accessed vii Feb 2016.

-

Dudley Metropolitan Borough Council (2014) 2011 Census, Available at: http://world wide web.dudley.gov.united kingdom/community/demography/2011-demography/. Accessed 7 Feb 2016.

-

Algan Y, Bisin A, Manning A, Verdier T. Cultural integration of immigrants in Europe. Oxford: Oxford University Printing; 2012.

-

Cummins S, Macintyre Southward. Food environments and obesity-neighbourhood or nation? Int J Epidemiol. 2006;35(1):100–4.

-

Dustmann C, Frattini T, Lanzara G. Educational achievement of 2nd-generation immigrants: an international comparison. Econ Policy. 2012;27(69):143–85.

-

Dalton RJ. The skilful citizen: how a younger generation is reshaping American politics. second ed. Us: CQ Press; 2015.

-

Myrvold K, Jacobsen KA. Sikhs in Europe: migration identities and representations. England and USA: Ashgate Publishing; 2013.

-

Crossley N. In the gym: motives, meaning and moral careers. Body Soc. 2006;12(3):23–50.

-

De Visser R, McDonnell EJ. "Man points"masculine capital and young men's health. Wellness Psychol. 2013;32(1):5–xiv.

-

del Aguila 5. Beingness a man in a transnational earth: the masculinity and sexuality of migration. New York and Oxon: Routledge; 2013.

-

Keeler SJ. No job for a grown human': transformations in labour and masculinity among Kurdish migrants in London'. In: Ryan Fifty, Webster W, editors. Gendering migration: masculinity, femininity and ethnicity in post-war Britain. England and U.s.a.: Ashgate; 2008. p. 191.

-

Implications for secondary pedagogy', Tin can J Educ. 25(2), pp. 112–125.

-

Macey M, Carling AH. Indigenous, racial and religious inequalities: the perils of subjectivity. U.k.: Palgrave Macmillan; 2010.

-

Zakar R, Zakar MZ, Faist T, Kraemer A. Intimate partner violence against women and its related immigration stressors in Pakistani immigrant families in Germany. Springer Plus. 2012;1(5). https://doi.org/10.1186/2193-1801-ane-5.

-

Johnston R, Forrest J, Poulsen M. Are there ethnic enclaves/ghettos in English language cities? Urban Stud. 2002;39(4):591–618.

-

Webster C. Race, space and fear: imagined geographies of racism, crime, violence and disorder in northern England. Capit Class. 2003;27(two):95–122.

-

Peach C. Glace segregation: discovering or manufacturing ghettos? J Ethn Migr Stud. 2009;35(9):1381–95.

-

Lan PC. White privilege, language capital letter and cultural ghettoization: Wester loftier-skilled migrants in Taiwan. J Ethn Migr Stud. 2011;37(twenty):1669–93.

-

Castleden H, Garvin T, Nation HF. Modifying Photovoice for community-based participatory indigenous inquiry. Soc Sci Med. 2008;66(6):1393–405.

-

Sandhu A, Ives J, Birchwood One thousand, Upthegrove R. The subjective experience and phenomenology of depression post-obit first episode psychosis: a qualitative study using photo-elicitation. J Bear upon Disord. 2013;49(i–3):166–74.

-

Achterberg CL, Arendt SW. The philosophy part, and method of qualitative inquiry in research. In: Monsen ER, Van Horn L, editors. Enquiry: successful approaches. USA: American Dietetic Clan; 2007. p. 67.

-

Beach MC, Rosner Thousand, Cooper LA, Duggan PS, Shatzer J. Can patient-centred attitudes reduce racial and ethnic disparities in care? Acad Med. 2011;82(ii):193–8.

-

Lavery JV, Tinadana PO, Scott TW, Harrington LC, Ramsey JM, Ytuarte-Nunez C, James AA. Towards a framework for community engagement in global wellness research. Trends Parasitol. 2010;26(half-dozen):279–83.

-

Campbell C, McLean C. Ethnic identities, social upper-case letter and health inequalities: factors shaping African-Caribbean participation in local community networks in the Great britain. Soc Sci Med. 2002;55(4):643–57.

Funding

No funding was obtained for this study. Information technology was completed as function of a PhD as function of a studentship at the University of Birmingham, College of Medicine and Dentistry.

Author information

Affiliations

Contributions

Wide conceptualisation of the report and methodology was developed past PG, LT and SG. The research focus was farther developed by FK alongside PG, SG, AL and MS. Data collection and analysis was led by FK while data interpretation was completed with input from PG, SG, AL and MS. The paper was written past FK with all authors approving the final manuscript.

Writer'southward information

N/A

Corresponding writer

Ethics declarations

Ideals approval and consent to participate

Ethical approving was given by The Academy of Birmingham Science, Technology, Technology, and Mathematics Upstanding Review Commission application number: ERN_13–0450. All participants provided written consent to take function in the research and were informed of their correct to withdraw.

Consent for publication

All participants provided written consent to take part in the research and for their interviews to be used anonymously for publications. All authors take consented to the publication of this work.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could take appeared to influence the work reported in this newspaper.

Additional information

Publisher's Notation

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Additional file ane.

Interview guide. A copy of the interview guide tin can be provided upon request.

Rights and permissions

Open Admission This commodity is licensed nether a Creative Eatables Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(southward) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and bespeak if changes were made. The images or other 3rd party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is non included in the article'due south Creative Commons licence and your intended utilise is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you volition demand to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/four.0/. The Creative Eatables Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

Reprints and Permissions

About this article

Cite this commodity

Kokab, F., Greenfield, Due south., Lindenmeyer, A. et al. Social networks, wellness and identity: exploring culturally embedded masculinity with the Pakistani community, West Midlands, Great britain. BMC Public Health 20, 1432 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-020-09504-9

-

Received:

-

Accepted:

-

Published:

-

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-020-09504-9

Keywords

- Qualitative

- Pakistani

- Men

- Social capital

- Identity

Source: https://bmcpublichealth.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12889-020-09504-9

0 Response to "Staying Healthy in Immigrant Pakistani Families Living in the United States"

Post a Comment